Free Exposure Therapy

How to fight your dad - and win

“You’re a failure,” he screamed at me. Red faced, spit flying from his mouth, hands balled into fists as he stared me down. “You never amounted to anything. And you don’t come home to visit!”

I took a breath. Then I yelled back, just as loudly. “Don’t you want me to be happy?? I’ve followed my own path. I never wanted to hurt you. But I like my life. Would you rather I do what you want, and be miserable?”

He opened his mouth to respond. I felt my heart start to beat faster and my hands start to tremble. I was getting flooded.

“Can we take a pause?”

Immediately, my opponent sat back. The color faded from his face, and he took a deep breath. He was shaking too.

The other people in the Zoom room let out the air they’d been holding.

“Wow, that was intense,” one said. “Your dad is really like that?”

M, the Asian man who had been role-playing his father, let out a short laugh. “Yeah, he really is. He’s angry at me for not following the path he wanted me to. He thinks I’m a failure - and he doesn’t mind saying so.”

“Let’s move into a debrief,” I suggested.

The other participants nodded - some new, some returning for the nth time to this practice. They were here to face their demons: the difficult people in their life, with whom any conversation would end in a fight. Despite the intensity of that topic, every one of them looked delighted to be there.

We began the debrief. As always, I checked in with the antagonist first. “M, as your father, did anything I said or any tool I tried make an impact?”

“It did, actually,” M said, surprising me. “I didn’t show it in the moment. But knowing my father, he would have taken some of these things home and reflected on them later. You saying that you were happy about your life made me soften and consider, at least on the inside.”

“Wow, I had no idea. You just seemed angry. But I’m glad; I was trying to find something you’d actually care about.”

“How was the fight for you?” M asked.

“I got really triggered by the end,” I said. “That’s why I paused - I stopped being able to think, which is when these role-plays become less useful. It’s hard to make new choices when I’m flooded. Before that…well, I found it hard to feel empathy for your dad. I think finding more of that would have helped. I did feel like I really found my own center, though. As a conflict-avoidant person, that felt good - to stay grounded.

“Is there anything y’all noticed?” I asked the rest of the group, who had been watching intently.

They shared about their own attempts to keep themselves calm during the scene. With prompting, they named moments they’d seen which seemed like potential points of connection, and we brainstormed techniques that M could try during his next argument with his dad (because, he agreed, there was sure to be one). Everyone was energized and contributing, even those who had never been to a Fight Lab before.

When the shares were over, I turned to M. “Okay - ready to try it yourself?”

He took a deep breath, rolled his shoulders, and nodded.

I turned to the group. “Who wants to play M’s dad?”

Fight Better, Together

At Authentic Revolution, through years of leading conflict courses, we’ve discovered that many fights are inevitable. They’re recurrent, they stem from base-level differences, or they’re across an imbalance of power. Practicing fights ahead of time makes them easier to confront when they arise.

Good connections aren’t about avoiding conflict. They’re about fighting better.

My partner Geof and I, along with a team of other amazing facilitators*, have led hundreds of free Fight Labs over the past 5 years. We’ve mostly done them online for the public (they happen every week on Wednesdays at 12 CT!) but we’ve also held them at festivals, dance weekends, burns, and for companies such as College Essay Guy, ART International, and Dell. Everywhere we go, the simple format just works. The most staid of businessmen end up joyfully shouting at each other as they practice conflicts they’ve held for years. Other organizations have started sending their own facilitators to our events.

I’m choosing to write about the Labs this week because, one, the practice has been so deeply impactful for me that I want to convince you to attend.

Two, I want to explore a question I and others have had about of the labs: is it useful to practice fights? Does it just re-traumatize participants? How resilient are people, really, when it comes to their deepest relational fears?

Before we get into that, let me tell you about Fight Lab.

A History of Conflict

We started Fight Lab during the pandemic, as part of a program we led and developed for the sensemaking organization Rebel Wisdom. Over time we brought that program, the Art of Difficult Conversations, to our own audience. Fight Lab became a standard even during the seasons we didn’t run the course. It has become our gift to the community - always free, always open to whoever wanted to attend, and so beloved that even the facilitators volunteer their time.

We started varying Fight Labs for 1:1 situations with Facilitation Fight Labs for group-leadership difficulties. We’d work with any situations participants brought. In the Fight Labs, we confronted bad landlords, abusive parents, wayward children, and sexist colleagues. In the Facilitation Fight Labs, we addressed overtalkers, participant conflicts, leadership takeovers, social justice challenges, even facilitator harassment. As long as it was a real situation that someone had or was going to experience, it was fair game.

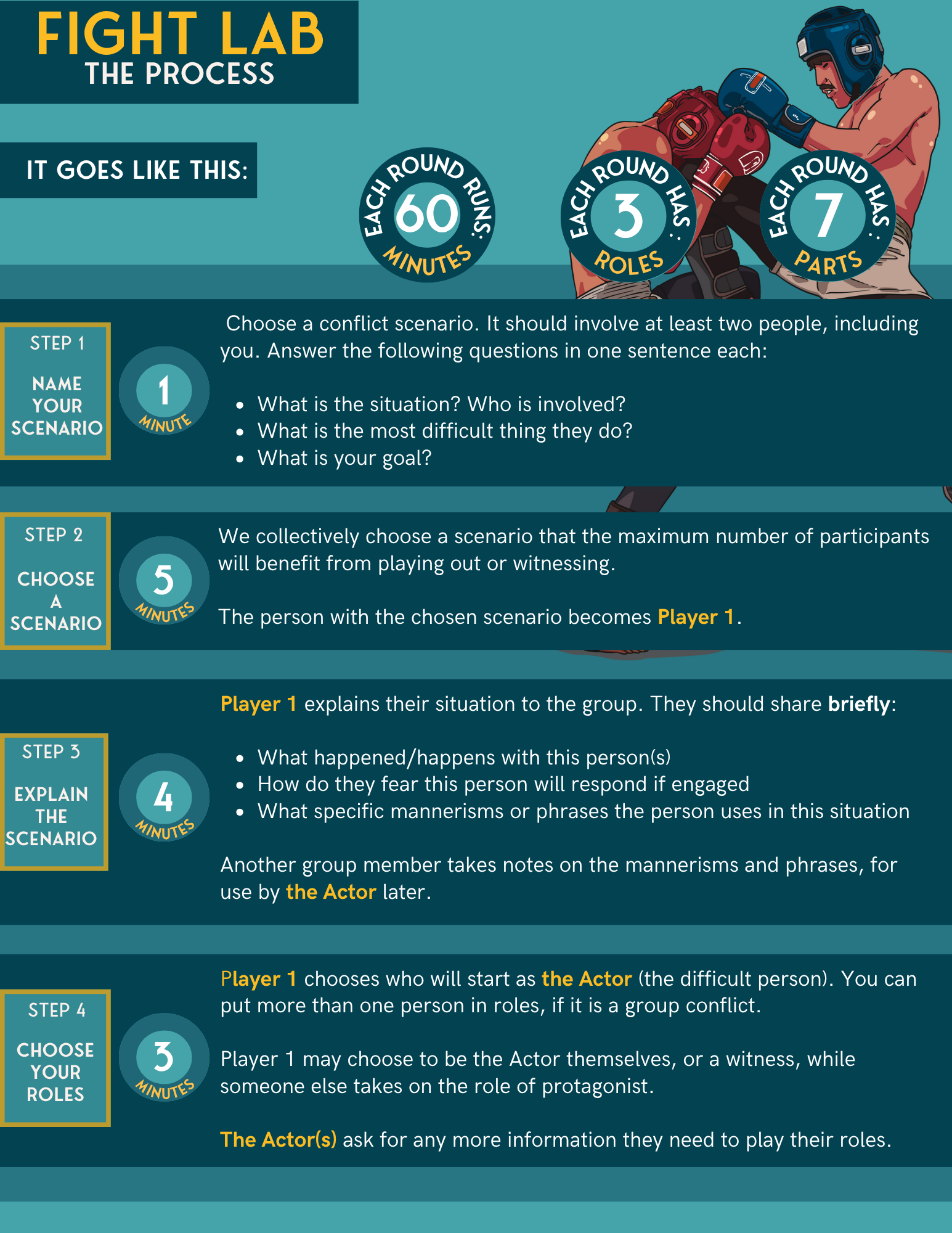

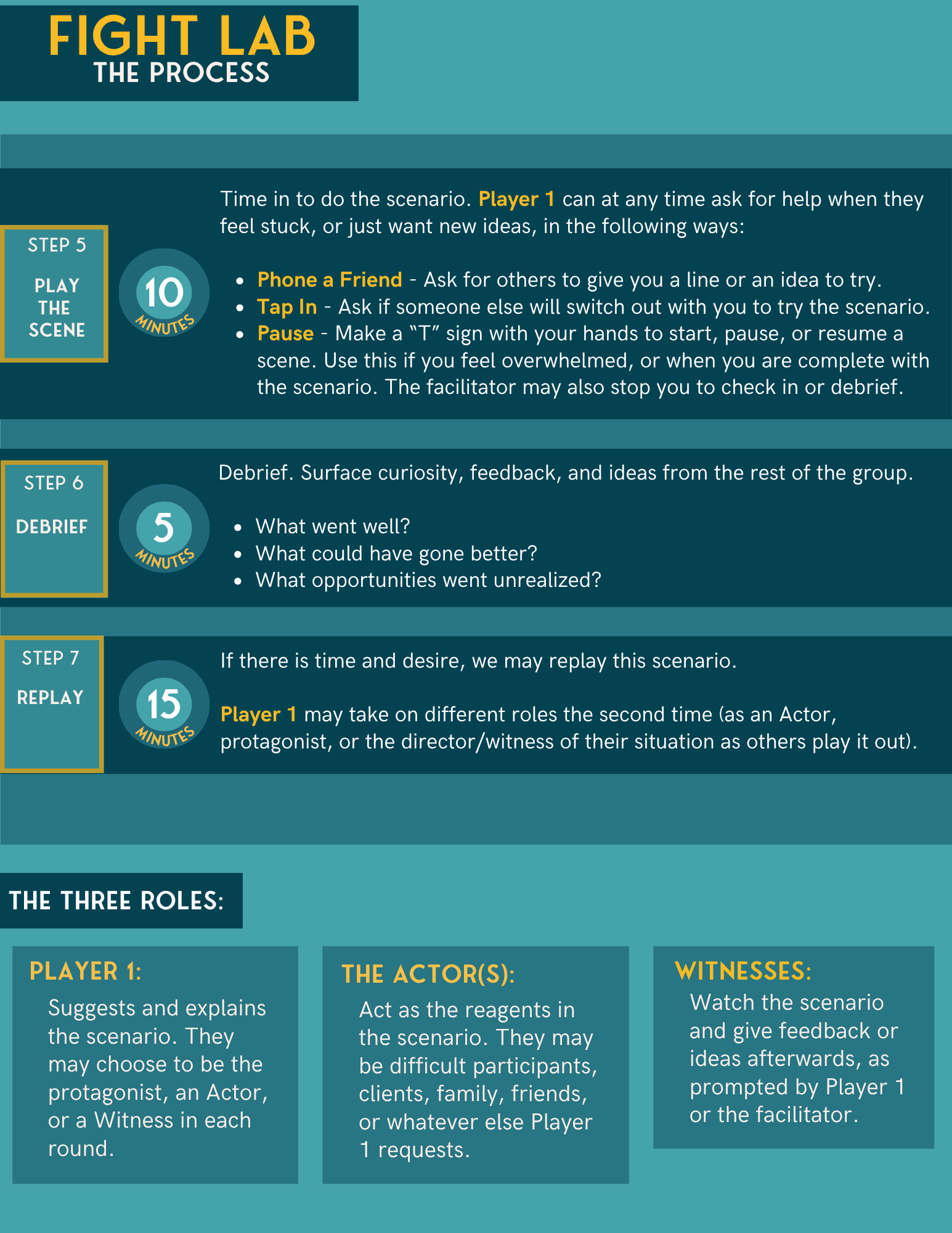

Here’s the format of a Lab:

The process gets even more fun (IMO) in the facilitator version, where the whole group is involved in upping the ante on the scenario. We might start with one challenging participant, and then add other group members who support one side or the other, until it looks just like the Protagonist’s worst nightmare of leadership. Then we bring the energy down and see what lessons they learned from playing a scene in real life that has probably often played in their head.

Reading this, you might think it sounds terrible. Why would anyone subject themselves to the torment of seeing their fears become reality?

First of all, Fight Labs are the best way I’ve ever seen of improving conflict skills. They’re especially powerful when used in conjunction with our conflict course. But even without teaching tools, I’ve seen participants practice and then actually have conversations that they’d avoided for years - or even decades.

So often, we’re so scared to fuck these conversations up that we never even let ourselves try to have them. We accept disconnection, powerlessness, or mediocre relationships over the potential of making things worse.

Additonal Read: Training Anger Management | Read full story →

But again and again, I’ve seen people play out their deepest relational terrors in these Labs…and when they’re in the moment, in the fire they’ve feared, they actually know what to do. Or if they don’t, someone else in the group does. We’ve all dealt with conflict. We become each others’ teachers in it.

The point in a Fight Lab is not to get the right answer or do it perfectly - it’s to try something new. When we break a habituated pattern of response, we have space for a new response. New responses start to build new neurological pathways. All of a sudden, instead of having just one way to address a trigger scenario, we have two, or three, or more. And as Geof likes to say, “The person with the most options, has the most power.”

So. Let’s get to the big question:

Is this safe?

The common belief these days seems to be that people are fragile. We are easily traumatized, and should be kept from unsafe situations, or anything that could potentially trigger us. Given this, it seems amazing that we’ve run hundreds of Fight Labs - often playing with situations of abuse, sexuality, power, or politics - without a single negative breakdown. We often get tears, but never hear that we’ve intensified someone’s trauma. We usually hear that the act of empowering oneself in the conversation is healing, even when it brings up pain that people have tried to avoid.

But, let’s be honest. You don’t come to my Substack for firsthand data. You come for the 🤓RESEARCH🤓. Let’s see what it says about roleplay’s use in treating trauma and PTSD.

The Nerd Stuff

Role-play is, essentially, a form of exposure therapy. According to one article, Bessel van der Kolk, van der Hart, and Burbridge (1995) name two conditions for this kind of experiential trauma processing.

-

The client must engage in activities that access the fear-memory.

-

The client must successfully cope with the memory, and experience mastery over their symptoms.

Role-play “gives us the opportunity to suspend (trauma) in time, allowing one to study a memory in its concrete form” (Dayton, 1994, p. 3). It externalizes trauma into a workable environment, where we can stop, examine, and change the circumstances.

The field that has probably used role-play the most in psychotherapeutic treatment of adults is that of psychodrama. I recently attended a training in this modality, and was shocked at how much we had accidentally replicated its formula in the Fight Labs!

One study of psychodrama, conducted in an inpatient substance abuse treatment facility, showed a 20% decrease in PTSD symptoms for a pre-pandemic cohort and an almost 25% decrease in a pandemic-era cohort. These results were found after just 2–3 weeks (4.5 group sessions) in the program. A similar study showed a 52.7% decrease in PTSD ratings.

Now - obviously, exposure therapy has its risks. If not practiced in a safe environment, where participants feel protected and at choice in their actions, it can re-traumatize people instead of helping them to heal. I’ve seen this happen several times in lightly-structured vulnerability containers such as circling.

There are a few techniques that we employ to keep Fight Lab on the side of trigger and not trauma:

-

We structure the practice tightly and clearly, to separate experiencing a trigger from verbally processing it, and both of those from receiving others’ perspectives on the scene. We’ve heard that the specificity of the container helps participants to feel held.

-

We encourage participants to pause the scenario if they are feeling flooded or overwhelmed. We tell them, “It’s not useful to keep going if you can’t think. If you can’t think, you can’t make new choices, and you are likely just to re-traumatize yourself.” If a participant seems flooded and doesn’t pause the scene, the facilitator will pause it for them to check in.

-

With particularly intense scenarios, we do grounding practices for the group afterwards. We’ll invite people to take a breath, shake their bodies, hum, or put on a song to dance it out. Sometimes we’ll give appreciations to the person who played the scenario, if they need comfort. If in person, we offer touch.

-

We give people space to have reactions. The plan is always secondary to the people. If someone is in a big experience, we make time for them to have it.

Beyond this, we don’t caretake. We don’t double-check that everyone is okay. We don’t offer sympathy to the person who brought the scenario, no matter how fucked-up we think their situation is; we only share our own impact, which might be anger or pain. We don’t try to solve them. We assume that everyone can hold their own experience - and so people do.

Fight Lab has shown us that we are, all, stronger than we think. When we’re faced with what we avoid, we don’t back down - we address it head on. We find a new path. And, as with all connection ruptures, what was caused by relationship is best healed in relationship.

Your Loving Thought-Dom,

Sara Ness

* shout out to our amazing facilitation crew Erin Root, Blair Lineham, Denise Morgan, Jason Jedrusiak, Laura Tatar, Kaela Atleework, Laura Tatar, Rachel Madore, Adrian von Engstrom, and all the Authentic Leadership Training facilitators who helped develop and lead Block Ops, the precursor to Fight Labs. Y’all are wonderful - thank you for helping us keep this event alive!

Responses