Training Anger Management

How does state-dependent learning affect skill-building?

Imagine this.

You take a well-regarded communications course and learn the skills of curiosity, empathy, and self-expression. You come home and use the skills with your partner, which they love. Until…things go wrong.

You’ve been practicing, and feel like you’re really getting a hang of these tools. But, a few days later, your partner forgets about a work party of yours and double-books themselves. You’re forced to go alone. Almost everyone else has a date, and you feel awkward.

When you get home, you yell at your partner. “How could you embarrass me like that??”

They wave their hands, trying to calm you down. “It wasn’t intentional. I forgot I had another commitment.”

You’re on a roll now, though. “This always happens. You put your social commitments over mine. This relationship feels so one-sided sometimes. I do such nice things to care for you, and then when I need you, where are you?”

Your partner says, “Calm down, honey. Use some of those great communication tools you learned at the workshop last week.”

This only incenses you further. Who are they to tell you to calm down? To use communication tools? THEY need tools, not you!

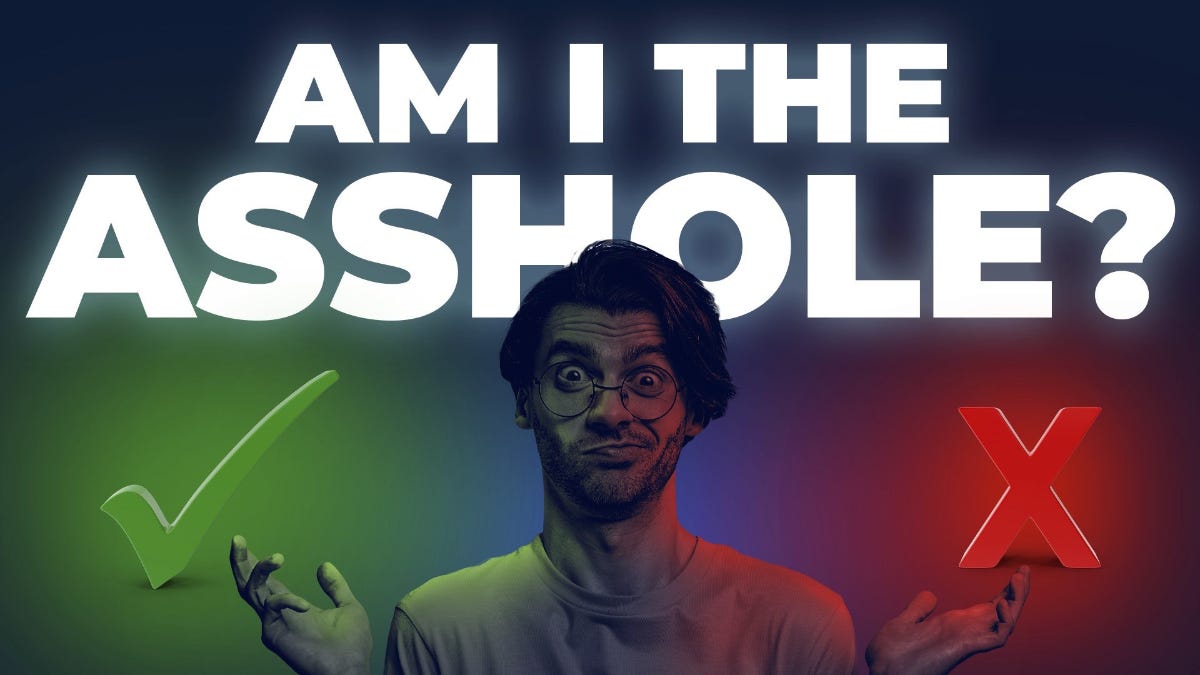

You’re seeing red. You know you’re being a bit of an asshole, and are probably going to regret this later. But you can’t seem to stop yourself. You can’t find your curiosity or your empathy. Your self-expression has no bounds.

You trained so hard - why can’t you access those well-curated, well-paid-for tools now?

Fighting Better

I and my husband have been teaching conflict trainings for the past 4 years. We’ve had about 400 students go through our courses, and hundreds more attend the Fight Labs we’ve held online for even longer. (They’re free - join us for one!) For those classes, one of the biggest challenges we’ve had to overcome is: how do we get students to apply skills they learn in a regulated state to situations where they are very upset?

If you’ve ever been angry, you know that you lose access to a lot of your curiosity and empathy when you’re triggered. You may care about the other person(s) you’re fighting with, but in the moment, you can’t move your attention outside your own sphere. (Check out this previous Substack article for the neurobiology of this.)

For this reason, Authentic Relating and Circling aren’t great conflict tools. We had to turn to the literature on negotiation, mediation, and de-escalation to find better ones. But even after we found the tools - which we teach in our Art of Difficult Conversations course every year - we had an even trickier issue crop up.

Our students found the tools mentally fascinating. But we were pretty sure that when it came to actual fights, they weren’t being assholes any less than before.

(I use that phrase deliberately. In fights, we may think that the other person is the problem. But usually, unless we’re in a genuinely abusive relationship, it’s at least 50% us. Either we’re practicing bad communication when triggered, or we’re being “good” in a way that sets our partner(s) off.)

Why couldn’t our students apply tools they learned in class to their actual conflict scenarios?

To find out, I had to delve into the research on a psychological phenomenon known as “State-Dependent Learning”, or SDL.

This article is about what I found - and how we might be able to use it to help ourselves, and our students, learn better.

Sara’s Substack is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

The Church of SDL

The idea of State-Dependent Learning has been around since the 1700s. In 1784, French aristocrat Marquis de Puysegur conducted experiments on hypnosis. He found that subjects couldn't recall events from their hypnotic state until hypnotized again. Similar hypotheses and experiments were made about dreams, fugue states, and stimulus response up until the 1960s, when Donald Overton started running formal experiments on how drugs influence memory and learning. As one book defines it:

State-dependent learning is observed when subjects experience training under one of two internal states (a state induced by the presence or absence of a drug in Overton’s case) and [are] tested under the opposite internal state. The common finding is that when subjects are trained in a nondrug state and tested in a nondrug state, behavior consistent with training is observed. Conversely, if subjects are trained while in a drug-induced state (e.g., amphetamine) and tested while not in a drug state, a decrement in performance is typically observed…

…If the internal state of the subject during testing is the same as during training, regardless of whether it is a state induced by administration of a drug, performance consistent with training is observed.

In other words, if you’re put into a specific state to learn a skill, and then tested in the same state, you’ll do better on that skill than if your state is different between learning and testing.

State-dependent learning is similar to state-dependent memory, i.e. why you don’t remember what happened when you got drunk…presumably until you get drunk again. (I will now need to do a test in the next few weeks: get very drunk, do something dumb, then get drunk again to see if I can remember the details of what I did. For science!)

This effect has been most tested as it relates to drugs. For example, some researchers had men smoke either marijuana or a placebo, and then learn a task such as putting 7 objects in order. The next day, the researchers divided each group in two, and once again had half the men get high.

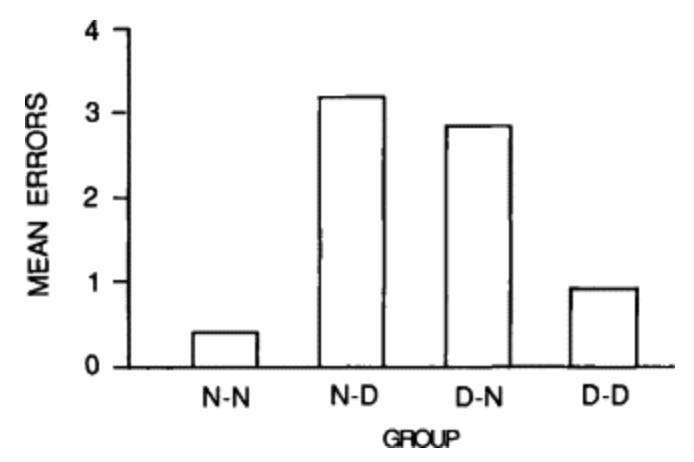

The results were conclusive: men made 3 times the number of errors when they HAD been exposed to marijuana during learning, and were NOT exposed during re-testing. This result held even though smoking pot had a minor negative effect on general recall, as the table below shows. “D” stands for Drug, “N” for No drug.

groups that smoked pot in one setting but not the other

In a short foray into “WTF Science”, these guys got off easy in just smoking pot. For some reason, the method of testing many of these hypotheses was to train participants in stressful environments, and then deliver shocks to their feet and/or immerse them in very cold water to see if researchers could replicate the stressful environment when testing learning recall. “Similar recovery effects have been found when retention deficits were induced with hypothermia (Vardaris et al., 1973)”. Ah, the halcyon days of Milgram and Zimbardo, before we had pesky things like ethical requirements and institutional review 🙄

And in other research I couldn’t help but cite: the effect of state-dependent learning is so widespread that it even shows up within the tiny worm c.elegans. When scientists tried exposing the worm to an odor (benzaldehyde) and ethanol at the same time, the ethanol had no effect on the worm’s reaction to the odor. But when the scientists pre-exposed the worm to ethanol and the odor at the same time, the worm would ONLY show an effect to the odor when ethanol was also present. So - get c.elegans drunk around a pretty odor, and it will fall for it again…but only if it’s drunk.

SDL has been so generally tested and proven, in so many animals (including humans), that it now seems likely that ALL memories and reactions are in some way state-dependent. A man who beats his wife when drunk can be a totally different person when sober. And if you teach someone skills while they’re regulated, they won’t remember them when they’re upset.

I see two ways of using this research in practice.

The first is in transferrable learning. The second, in habit and ritual.

A teaser of what we’ll talk about, if you are a paid ($5/month) subscriber:

-

How to fake anger response in the body

-

What early Circling and encounter groups did wrong

-

How to upset people JUST enough to train them

-

How master martial artists take tests

-

Why students during the pandemic got worse grades

-

Using your environment to cue state shifts

Let’s get to it!

Transferrable Learning

The most obvious lessons we can take from SDL are that, 1. Things learned in one state do not transfer well to other states, and 2. Things learned in one state DO transfer to the same state when experienced again.

Thus, it makes sense why learning anger management techniques while regulated wouldn’t help you manage your anger when triggered - or at least, not as well as if you learned the techniques while already upset.

But, what is “upset”?

Here is where things get REALLY interesting. I have to thank my dear friend Wouter Sledgers for this idea.

Our state can be mediated by many things. Ultimately, though, what we’re talking about with “state” is bodily response. Anger causes a spike in heart rate. Our palms get sweaty. Our cortisol levels go up. Our muscles tense.

Sound like anything else?

To quote an article from Counseling Perspective:

When you exercise, your heart rate increases and you experience shorter, shallow breaths. Your body naturally works to slow your breathing to a normal pace following exercising. This physiological response is similar to the response needed to calm down when you are feeling angry.

Intense exercise even causes a temporary increase in cortisol levels. The way our body responds to exercise is similar to how it responds during anger. During anger, muscles tense up, and respiration rate increases. This is due to the release of catecholamines like adrenaline and noradrenaline, which prepare the body for physical action.

Thus, the natural conclusion: having people exercise and then practice de-escalation or presence techniques may be an effective way to train a better anger response.

I could imagine other ways of achieving the same effect, that might be easier to replicate during workshops. Having someone beat on a pillow, for example, or do silent screams. Perhaps even getting people to frown, take short breaths, and growl would do the trick.

Then we have a more direct method: just get people angry.

In our workshops, we do this using a role-play method called Fight Lab. At basic: you explain a conflict to someone else. They roleplay you, while you play the person you’re in conflict with, to get inside their head and demonstrate their mannerisms to your partner. Then you switch roles: you try to deal with your difficult person while they try to make life hard for you. (Here’s a description of the event.)

This works most of the time, especially when you’ve got a really good coyote playing your difficult person.

But there are shorter methods too. For instance, Identity Triggers. You identify things that trigger you on a fundamental level, because they call into question what you hold dear about yourself. For instance: perhaps you get deeply triggered if people question your level of competence, because you see yourself as a competent person.

Then your partner takes that information and sets up a scenario where they can roundly insult your identity. You attempt to hold onto your sanity and create a good outcome. (These exercises all work better if one defines, in advance, the outcome that one wants to achieve.)

You could perhaps potentiate both of these by doing the above self-activation methods first. Or playing the Fuck Game, where someone says: “Fuck….[our political system, internalized racism, my mom for making me feel like a failure as a kid, etc.) and continues ranting about all the things upsetting them until they have no more fucks to give. Then someone else takes over. It’s a good game for getting your blood pressure up.

Here’s an example of how this works in a real scenario:

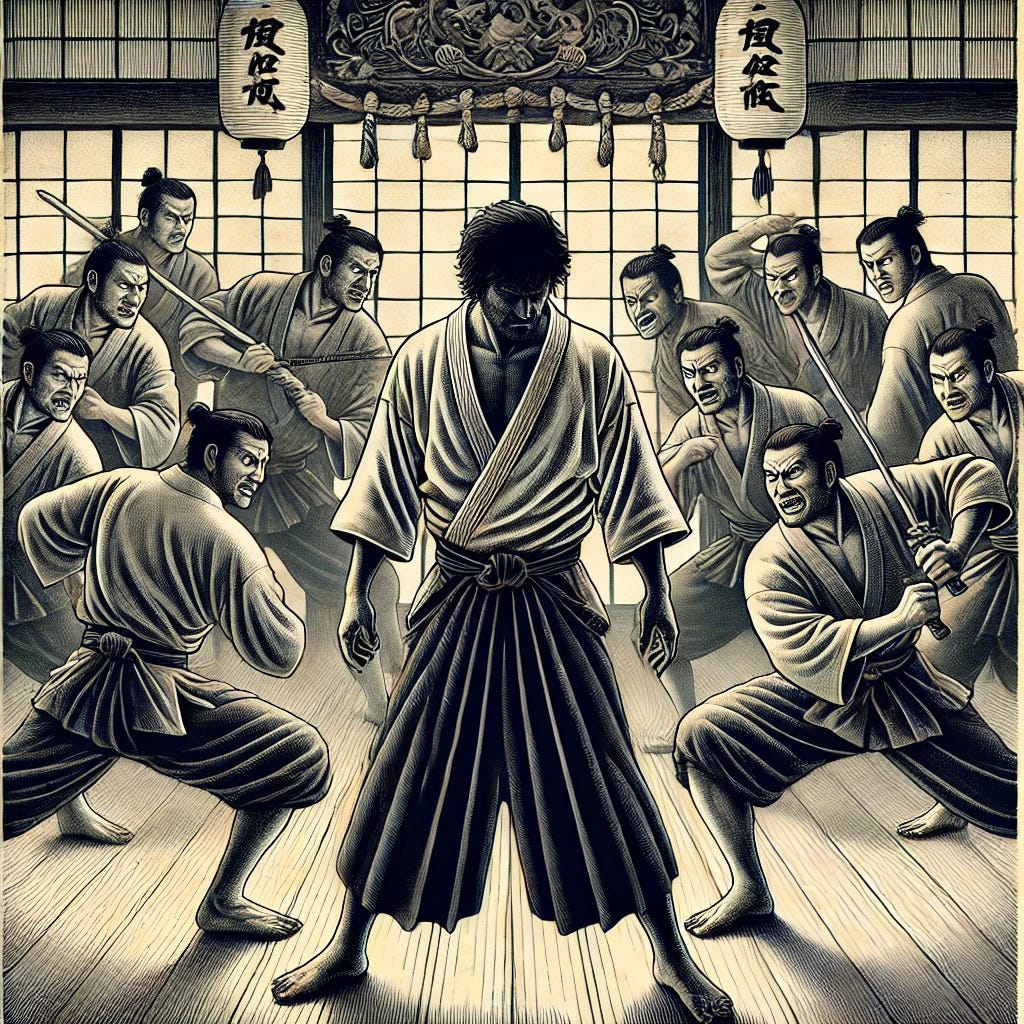

My dear friend Sarah Jack, who is the brilliant mind behind our social media account (which y’all should check out, her posts are both hilarious and informative), is also a high-level martial artist. She told me that for her martial arts tests, her instructors first exhaust the participants. Paraphrased:

They make you get it all out, until you have nothing left. They know that in a real fight scenario, you’re probably going to be exhausted and overwhelmed. They set up that situation before they test you. They know that you don’t rise to the occasion, you fall to your level of training.

A small caveat note here. In a wonderful workbook from SAMHSA, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, I found a couple myths about anger management. This gem stood out to me, as someone who has been told much about the early days of Circling and Encounter Groups:

Myth #4: Venting Anger Is Always Desirable. For many years, there was a popular belief that the aggressive expression of anger, such as screaming or beating on pillows, was healthy and therapeutic. Research studies have found, however, that people who vent their anger aggressively simply get better at being angry. In other words, venting anger in an aggressive manner reinforces aggressive behavior.

So - make sure you’re training the right things. People don’t learn to avoid a state by being in it more often. If you get people activated, it should be in order to teach them how to calm down.

Let’s move on to the second application I see for SDL…

Habit and Ritual

Let’s start this with a question. Why did students during the pandemic have such a hard time learning online, as compared to in the classroom? According to one meta-analysis:

Virtually all of these studies found that online instruction resulted in lower student performance relative to in-person instruction. Students in online courses generally get lower grades, are less likely to perform well in follow-on coursework, and are less likely to graduate than similar students taking in-person classes….Looking at student outcomes in Spring 2020 in Virginia’s community college system, Bird et al. find that the switch to online instruction resulted in an 8.5% reduction in course completion.

Part of this effect could be explained by the lack of peer interaction. But, one big affect was likely state-dependent learning.

Students were using the same medium and location that they used for other aspects of their lives - entertainment, information-gathering, and socializing - for going to class. Everything, absolutely everything, was on the computer. So, students had trouble paying attention and taking in information, because what they learned online blended together with everything else they did digitally.

According to one study, the most successful students were those who created rituals to differentiate their computer learning-time from their computer play-time and social-time. This might be making a coffee before class, putting on a specific background, playing a specific song, etc. They cued a state-shift that reminded their mind to pay attention.

Perhaps we unconsciously know this, and practice it through habit. For instance, I write at the same time every day. I light the same candle. I sit in the same spot on my couch, and look out the same window. This routine is a recurring stimulus that evokes a recurring state. If I’m away from my house, I at least play the same playlist I did when at home.

If habit and ritual can cue a state shift, we should also be able to use them for anger management. For instance, you could teach students that any time they feel their breath getting short in an argument, they use a breathing technique. Or, they could make an agreement with partners to set up a specific space and ritual for having tough conversations, one that reminds them to use pre-determined techniques like listening and curiosity.

One of my favorite ways I’ve seen this kind of cueing used comes from Frederick Laloux’ masterpiece Reinventing Organizations. He cites a company that uses a bell when tensions get high in a room. Until the echoes of the bell fade away, nobody can speak. Over time, the ritual of hearing the bell itself will likely remind people to de-escalate. A little Pavlovian, but what in here isn’t?

And now, to the close…

Thank you, readers, for accompanying me on this exploration. It helped me to piece out a topic I’ve wondered about for a long time, and come up with some new techniques I plan to use in my workshops.

If you take one thing away from this article, I think it should be the saying of Sarah Jack’s martial arts teachers: “We do not rise to the occasion. We fall to our level of training.”

Our level of training is state-dependent. We must train in the same environments where our triggers will occur. Only then will we master the skills, and provide the teaching, that we want to see in ourselves and the world.

Your Loving Thought-Dom,

Sara Ness

Sources Cited

Reilly, Patrick M., et al. "Anger Management for Substance Use Disorder and Mental Health Clients: Participant Workbook." Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2019, store.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/anger_management_workbook_508_compliant.pdf.

Hamer, M., et al. "The Effect of Acute Aerobic Exercise on Stress Related Blood Pressure Responses: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis." Biological Psychology, vol. 71, no. 2, 2006, pp. 183-190. PubMed, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18787373.

Bajandouh, Freya. "Can Exercise Help Anger Management & Reduce Rageful Outbursts?" Counseling Perspective, www.counselingperspective.com/blog/exercise-anger-management.

Cellini, Stephanie Riegg. "How Does Virtual Learning Impact Students in Higher Education?" Brookings Institution, Aug. 2021.

Urcelay, G.P., and R.R. Miller. "Extinction and Recovery of Responding." Learning and Memory: A Comprehensive Reference, edited by John H. Byrne, Academic Press, 2008.

Poling, Alan, and Jeffrey Cross. "Behavioral Pharmacology." Techniques in the Behavioral and Neural Sciences, vol. 6, 1993, pp. 1-25.

Timbers, T.A., and C.H. Rankin. "Habituation." Encyclopedia of Neuroscience, edited by Larry R. Squire, Academic Press, 2009, pp. 1049-1056.

Responses