Sifting the Sands

Researching Through the Noise

When we began designing The Art of Difficult Conversations, we thought we’d be curating from a deep and credible field. Conflict, after all, is hardly a new subject. The literature goes back actual millennia. Entire professions exist to manage it, mediators, therapists, hostage negotiators, organizational consultants. Surely, we figured, someone had already done the work of integrating the best ideas from these eras, fields, and lineages.

Well, let me tell you, they hadn’t.

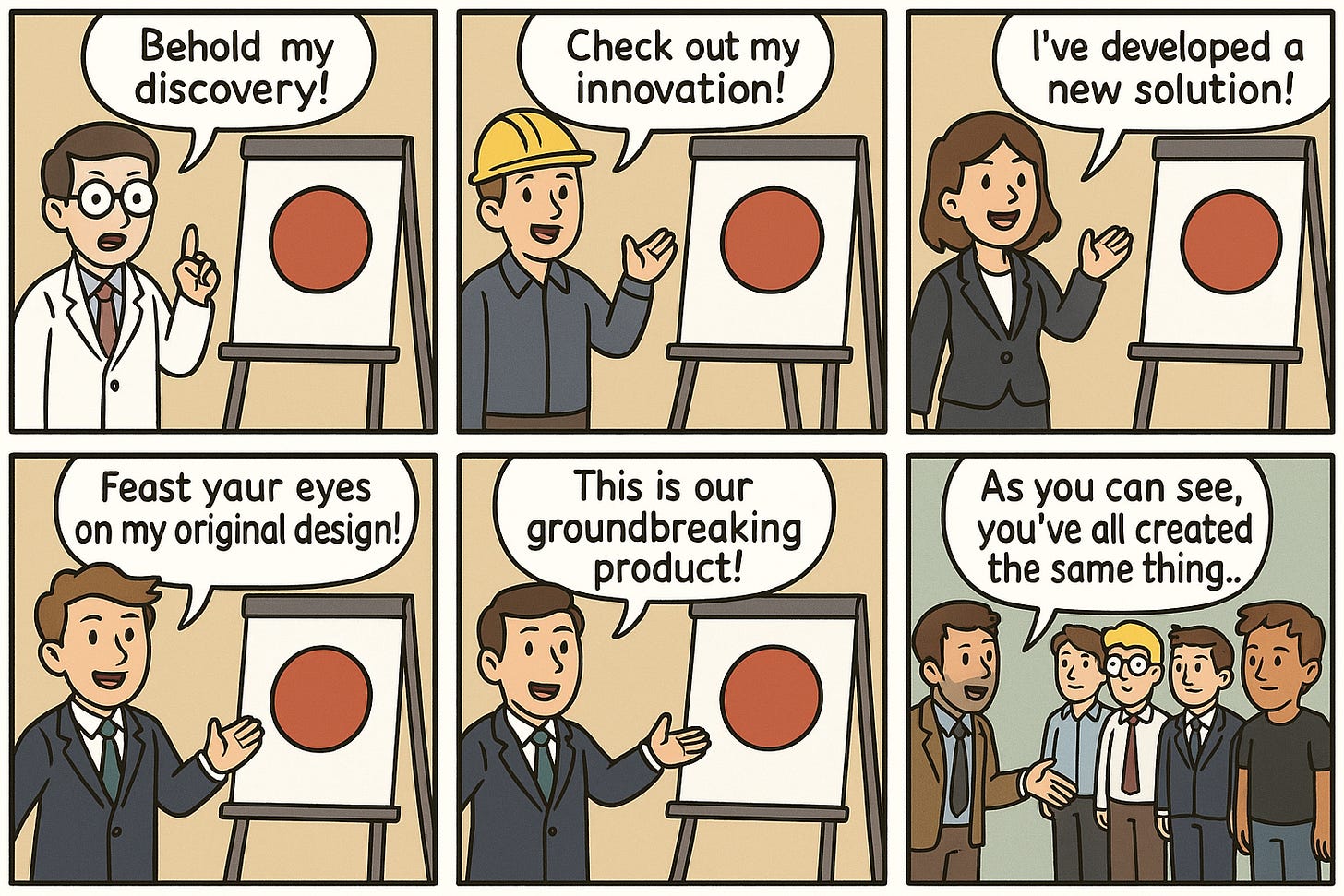

What we found was a field defined by fragmentation. Every discipline operated in its own language, siloed in such a way that the vernacular, terminology, and methodology often didn’t even conform well enough for search engines. For instance, the same approach or technique across fields may be commonly referred to as revealing, vulnerability, transparency, and self-disclosure. While you may be familiar with the terminology for the object of a conversational exercise, referred to alternately as the MDO (most desired outcome), settlement, zone of acceptance, goal, or area of agreement.

Therapists trained in emotional intimacy had never read the negotiation literature. Mediators fluent in interest-based bargaining knew almost nothing about attachment theory. Leadership trainers taught feedback delivery without addressing basic emotional regulation or identity triggers. And all of it was overgrown and comingled with compulsory doses of self-help content, branded, confident, regularly unsubstantiated, and often unreadable.

The problem wasn’t that there wasn’t good research. The problem was that no one had really collated it across the continental divides. No one made a bridge wide enough for a real human being to walk across.

So we started engineering.

A Tower of Babel

The deeper we went, the clearer the pattern became. Most approaches to conflict cluster in one of four silos. Each is valuable in its specificity and limited in its selectivity.

1. Psychological and therapeutic models treat conflict as a manifestation of unresolved emotional needs. These models emphasize empathy, safety, and attunement. When they work, they feel sorcerous and magical. But they often falter when applied to institutional or political conflict, where the personal dynamics are obscured by power, protocol, and finite objectives.

2. Negotiation frameworks like those taught in law and business schools treat conflict as a problem of interests and leverage. These models shine in adversarial settings. But they tend to assume rational actors and undervalue both emotional and relational complexity. Grab a bag of popcorn, kick back, and watch someone applying “principled negotiation” in a marriage.

3. Mediation and group process models excel at neutrality and facilitated dialogue. They offer powerful tools for third-party conflict resolution but often require an external referee. Most people don’t get to have one in real life, and if you thought that applying principled negotiation to marriage felt weird, watch someone try to navigate the power dynamics of attempting to both hold a neutral container and support their own interests simultaneously…

4. The self-help ecosystem borrows from all of the above at the cost of stripping most of the rigor and the context of application. This is the space filled with “communication coaches,” TED Talks, and frameworks with trademark symbols. TThis is the trendy lion’s mane latte shop where neuroscience meets social influence for peer-support therapy. Occasionally, something useful gets through or even coheres. But most of it is performative, untested, and/or sensationalized. Much of it works well in branding. A lot of it fails utterly in productive conflict.

We did not want to reject these fields outright. In fact, we wanted to honor the best of them. But we needed to go beyond their walls.

Under Pressure.

*Dun dun dun duh da duhn duhn*

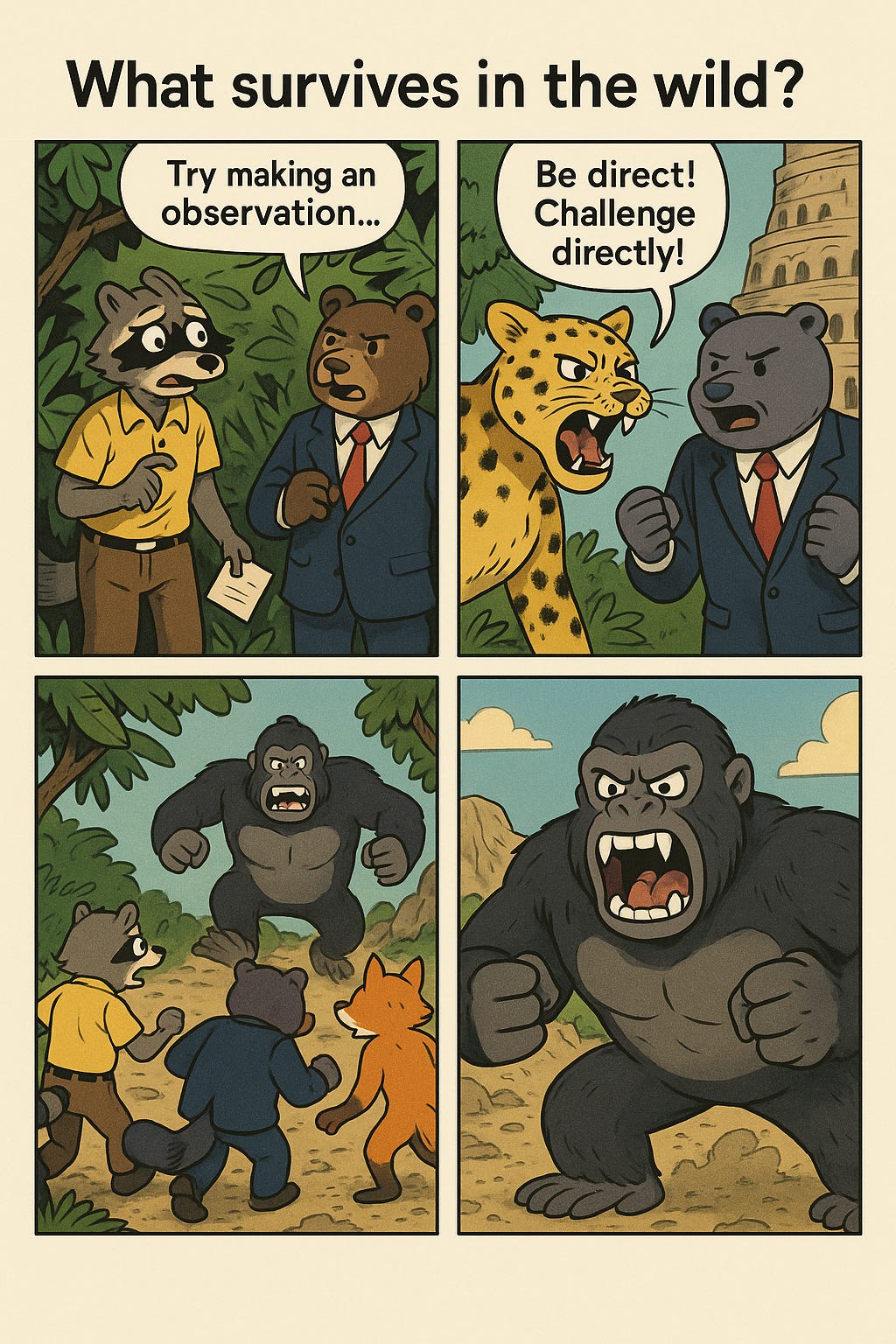

We started applying a simple standard. If a model or method could not be practiced under real tension, it did not make the cut.

There was a very eclectic blend of models, tools, and ultimatumist claims left on the cutting room floor.

One popular method encouraged people to follow a four-step communication protocol. Step one was “make an observation.” Step two was “name your feeling.” Step three was “express your need.” Step four was “make a request.” Clean. Elegant. But most people in real conflict do not have the executive function to remember four steps. Especially not in the middle of a fight. And even if they do, the tone of their voice will often matter more than the sequence of delivery. So, without the method and an understanding of intention, the actions are near irrelevant.

Another favorite of corporate training was this idea of “radical candor.” Say what you think. Be direct. Challenge with care. But no model that centers directness without deeply examining power, identity, and psychological safety is going to work across cultural or even social divides. What is “candor” to one person is “disrespect” or outright “violence” to another. What is “honest” in a closed performance review is “hostile” in an open project meeting. These models often reflect a narrow cultural context. Usually white. Usually male. Often managerial. I would know, I live that life.

So we asked a different question.

Not what looks good on a slide. (though my thousands of slides do care deeply about the answer to this question)

What survives in the wild?

Unexpected Convergences

The most resilient tools, ones that showed up across disciplines and maintained relevance across settings, were often the least flashy.

Mirroring, a simple reflection of another person’s words or tone, appears in hostage negotiation, couples therapy, and cross-cultural mediation. It works because it builds trust and slows escalation. FBI negotiators use it. So does the Gottman Institute. So does every good therapist you have ever met. Except that one. You know the one.

Framing, the act of naming the purpose or direction of a conversation, shows up in leadership communication, trauma informed practice, and political dialogue. A well timed reframe can shift a conversation from adversarial to collaborative in a single sentence. A well developed preframe can mean the difference between a well considered dialogue and a fist fight surprise.

Pacing and breath awareness, cornerstones of both somatic coaching and martial arts, are also essential in high pressure communication. So, they are taught to Navy SEALs in the same way as EFT clients. Remember, most breakdowns happen not because someone said the wrong thing but because they said the right thing with too much charge, too little presence, or without contextual awareness. All of which are hallmarks of emotional dysregulation.

There is no fancy acronym for these. No intellectual property. No specific certification.

Just attention. Just practice. Just rigor.

What We Built From

We ended up pulling from about a dozen primary sources. A few worth naming:

-

Chris Voss’s work in Never Split the Difference, not for its bravado, but for its clear articulation of psychological pacing and tactical empathy.

-

John Gottman’s decades of research on conflict patterns in long-term relationships, particularly his findings on emotional flooding and repair attempts.

-

William Ury and Roger Fisher’s framework from Getting to Yes, which remains the most credible articulation of interest-based negotiation.

-

Daniel Siegel’s work on neurobiology and interpersonal regulation, which gave me the language to connect emotional reactivity with cognitive narrowing or lensing.

-

Arlie Hochschild’s concept of emotional labor, which helped us explore how conflict is shaped by power and social expectation, especially in care centered roles.

So, we staked out the terrain, marked the crossings, and then we started building bridges between them.

A Note on Practice

None of this matters if you can’t embody the principles and tools.

That’s the last and most important filter we applied. It wasn’t just “Is this practical?” It became “Is this practiceable?” Can someone build muscle memory for it? Can they learn to feel the moment when a conversation turns and responds with intention, instead of reacting out of habit?

The point was never to deliver insight. It was to render insight and intuition reusable, replicable.

That is the work. With many of our students I found it was not learning more. It was practicing differently.

Because conflict is not just an information problem. It is a nervous system problem. And the best map in the world is useless if your hands are shaking too hard to hold it.

Responses